Nowadays fewer than one in five of the labour force are engaged in actually making things, in the sense of taking some raw materials and turning them into something else. The rest of us, if we are what economists call ‘active’, are instead selling stuff to each other, meeting demand for healthcare, education or hedonism, ensuring people can move around to assuage that demand, performing countless obscure tasks purportedly related to management and administration or acting out the role of wannabe ‘influencers’.

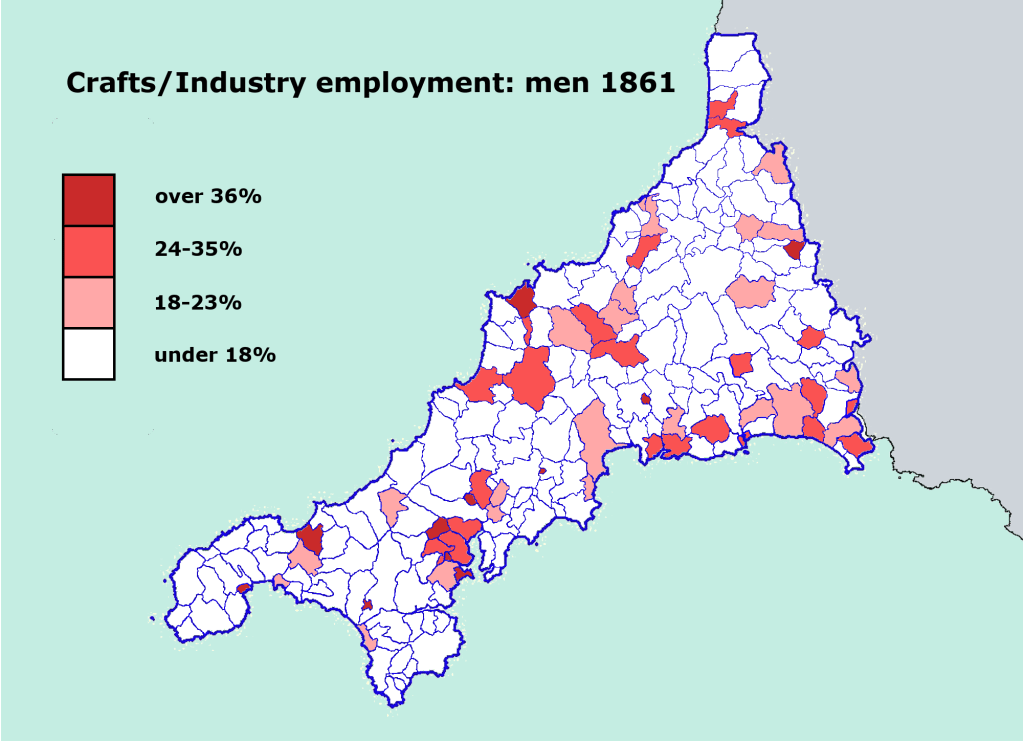

In fact, the proportion of the male workforce in the Cornwall of 1861 that was found in crafts and factory work was surprisingly similar – at 18 per cent. Of course, in those days finding, extracting or farming the raw materials involved a lot more workers than now and servicing the needs or desires of others far fewer.

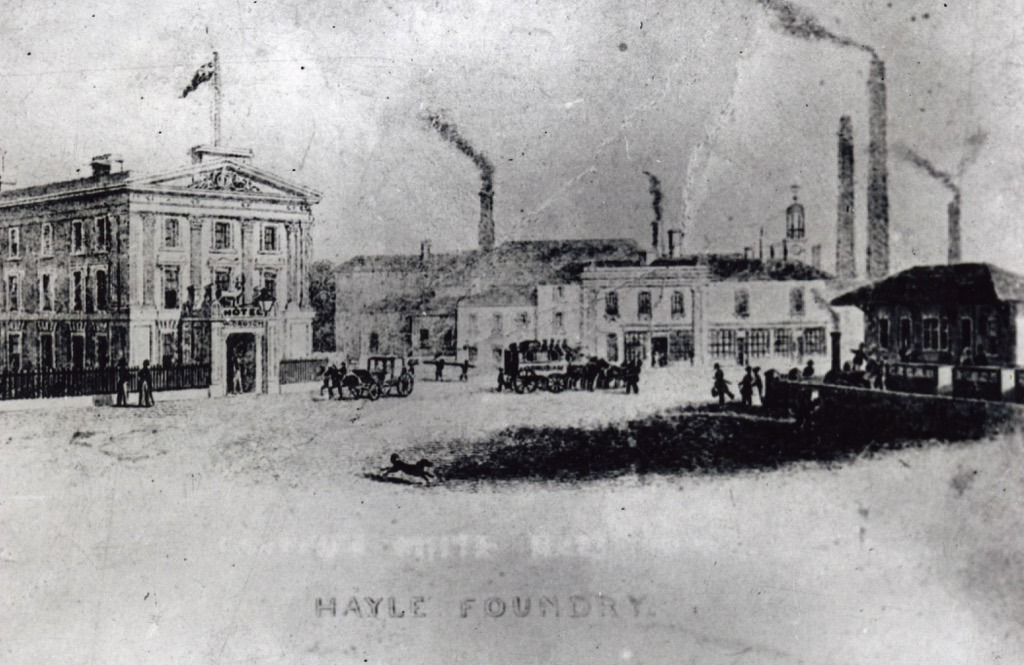

Most workers in manufacturing related jobs in Victorian Cornwall were traditional craftsmen – masons, carpenters, blacksmiths, shoemakers, tailors, shipwrights and so on. Work in factory industry was rarer and what there was – in iron foundries, tin smelting works, gunpowder or safety fuse factories – tended to be spin-offs closely connected to the local mining industry.

Craftsmen were concentrated in the towns of Cornwall. Helston, Truro and Penryn hosted the most with approaching a half of all men in those towns boasting a craft of some kind. The proportion of men in crafts and industry in some other places reflected the presence of specific industries. Phillack, including most of Hayle, was a centre of engineering as was Perranarworthal; the proportion in manufacturing in Grampound was boosted by local tanneries. Higher percentages in the coastal parishes of south east Cornwall, Padstow or near the Fal estuary reflected concentrations of shipbuilders, accounting for almost 1,000 men, or just over one per cent of Cornwall’s male workforce.

Meanwhile, those parishes dominated by either farming or mining tended to have lower proportions engaged in crafts and industry.

If you have found the material on this site of use then you may be interested in my recent books published under the Coserg imprint. For a list see here.