Stephanie Boland, ‘The “Cornish tokens” of Finnegan’s Wake: A journey through the Celtic archipelago’, James Joyce Quarterly 54.1-2 (2016-17), 105-118.

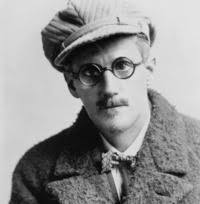

The novel Finnegan’s Wake was written by James Joyce over a 17-year period between the two world wars of the twentieth century. It was, depending on your view, either a work of ludic genius that experimented with and extended the frontiers of the English language, or a sprawling, baffling and insane mis-use of that same language. It’s also one of those books that most of us have heard of but few of us have ever tried to read.

Which means there’s plenty of scope for a whole academic industry to have arisen around the meaning of Joyce’s work. Stephanie Boland points out in this article how Finnegan’s Wake has hitherto been analysed in terms of the tension between its Irishness on the one hand and a cosmopolitan transnationalism on the other. Like other simple binaries this one has recently crumbled, replaced by the idea of a ‘more complex European network of cultural exchange’ purportedly underpinning the pages of Finnegan’s Wake. But in all this there has been little mention of Cornwall. Until now that is, as this article casts its critical eye on the place of Cornwall in Joyce’s work.

One of the many literary devices that Joyce alludes to in Finnegan’s Wake is that of Tristan and Isold. This has been viewed by Joyce critics as part of his European context. Yet, even though re-written in France, the story is set entirely in the Celtic archipelago – Cornwall, Ireland and Brittany – and moves between those locations. In Chapter II.4 of Finnegan’s Wake Joyce makes use of the Tristan myth but employs multiple identities in place of the voyaging that occurs in the source. His characters become Tristan avatars, the publican HCE being King Mark, his son Shaun Tristan and daughter Issy – well, that’s fairly obvious.

In this construction Cornwall has a role, albeit a minor one. Stephanie Boland digs out some possible references to Cornwall. There is mention of Tintagel, also St Just and St Austell, St Ives, Landsend and the River Fal. Cornwall appears as ‘Corneywall’ or ‘Cornerwall’, while ‘hubba’ [sic], a ‘cry raised by fishermen’, also gets a mention. These are the more explicit references. Stephanie Boland’s argument about Cornwall’s place in Joyce’s work is supplemented by analysis of his voluminous letters and notes, on which Finnegan’s Wake was based. These display an interest in Cornwall, its language and its geography as well as notes on Tintagel and the Arthurian legend.

According to this article Joyce drew on some common aspects of Irish and Cornish revivalism to locate Cornwall ‘as a Celtic nation to complicate and ramify the Cornish aspects of his characters’. This was expanded to include myths from other Celtic nations and references to the familiar drowned land, Lyonesse. Joyce’s references to Cornwall and his employment of the Tristan myth were neither an example of internationalism nor Irishness but part of a challenge to the ‘traditionalist and insular perceptions’ of Celtic culture that Joyce disliked in contemporary Irish revivalists. That frustration however ‘did not extend to resentment of the idea of a shared Celtic cultural heritage’. In this more outward Celtic identity it seems that Cornwall played a central part.