The Cornish identity rests on three foundations.

First, there’s a package of behaviours, attitudes and attributes associated with being ‘Cornish’. For example these might include

- a fondness for some types of music – male voice choirs for those of a certain age; ‘Celtic’ song and dance for another

- a tendency to prefer the rugby code of football, providing the trigger for those occasions in the 20th century when Cornishness was most prominently displayed publicly

- a predilection for items of diet such as pasties or saffron buns

- a particular accent or use of dialect words

- or even an indefinable sense of humour

Second, there’s the Cornish language, closest to Breton and with some similarities to Welsh. This is an inescapable part of our lives as it surrounds us on signposts and in some folk’s surnames, giving Cornwall an air of difference. It’s also given rise since the 1870s to a revivalist movement, and a small number of speakers of revived Cornish.

Third, there’s our history. Not the past, which doesn’t change. But the stories told about that past, which do. In recent years, some have been become more forthright in arguing that the history of the Cornish is a history of struggle against external power. The robust nationalist histories written by John Angarrack (for example Our Future is History), are good examples. But other histories have appeared and they all show us the ways in which Cornwall’s experience differed from its neighbours.

The first of these three elements, that blend of ‘Cornish culture’ sometimes described as ‘classical’, can co-exist with a regional or even a county identity, and nestle within loyalty to the British state, to the monarchy, or even to ‘England’. The second and third are more likely to give rise to a Cornish national identity, one that doesn’t view Cornwall as part of another nation but a nation in its own right.

The number of native Cornish has declined since the onset of mass in-migration in the 1960s. From near 80% in the 1950s, it has fallen to somewhere between 40% and 50% nowadays. However, despite or perhaps because of this, there is evidence from the last decade for a rising sense of subjective Cornishness. Surveys of the ethnicity of schoolchildren (or their parents) indicate a steadily rising propensity to define themselves as Cornish.

Recent censuses show that this was not limited to schoolchildren. One in seven people in Cornwall, possibly as many as one in three of the native Cornish, are prepared to go to the considerable trouble (in the disgraceful absence of a straightforward tickbox) to define their ‘national identity’ as Cornish. Moreover, this percentage has more than doubled when compared with the number of those who declared a Cornish ethnicity in the 2001 Census and in the 2010s the proportion of those claiming to be ‘Cornish only’ rose from 10% to 14%.

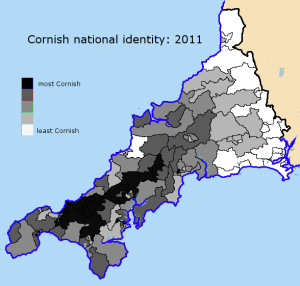

The map of the Cornish identity shows a marked west-east gradient, with the core Cornish population being in an inland band to the west. In this respect it echoes the linguistic history of Cornish. The Cornish language died out first in the east, before retreating westwards. The exceptions are those places where tourism has brought population shifts in its wake, such as Lelant/Carbis Bay, the Newquay area, parishes north of the Helford, and St Austell Bay.

On the other hand, those wards where most people are likely to declare a Cornish national identity (without adding English or British) are in the old central mining district of Camborne-Redruth and parrts of the clay country. These remain Cornwall’s centrally Cornish districts.

2 thoughts on “The Cornish identity”