Matteo Ravasio, ‘Food landscapes: an object-centered model of food appreciation’, The Monist 101 (2018), 309–323.

At last, some academic interest in the pasty! This article promises to use the Cornish pasty to illustrate how an ‘object-centred model’ of aesthetic appreciation can be applied to ‘food landscapes’. Landscape is a deliberately chosen descriptor as the model was originally devised for the appreciation of nature.

Basically, it rejects anthropocentric approaches such as those drawn from art appreciation and calls for a shift in perspective. This should take into account the material, historical and social context of the object of appreciation itself. The implication is that as our knowledge of the object grows we can achieve a better position from which to appreciate that object aesthetically, perhaps in novel ways while escaping older fixed assumptions.

This all sounds plausible enough if a little vague. The article moves on to list six ‘desiderata’ for appreciating food, or any other object for that matter. These are intentionality (the material aspects of food production and consumption), historicity, normativity (the accepted rules of presentation or ingredients), authenticity, appropriation (the conscious modification of a food) and meaning.

Some of these are then applied to the pasty. However, while promising a proper feast the article delivers disappointingly sparse sustenance. Strong on theory, it offers little at the empirical level. Discussion of the pasty is relatively perfunctory and, while broadly accurate, the account is based on a superficial reading of both its history and that of Cornwall.

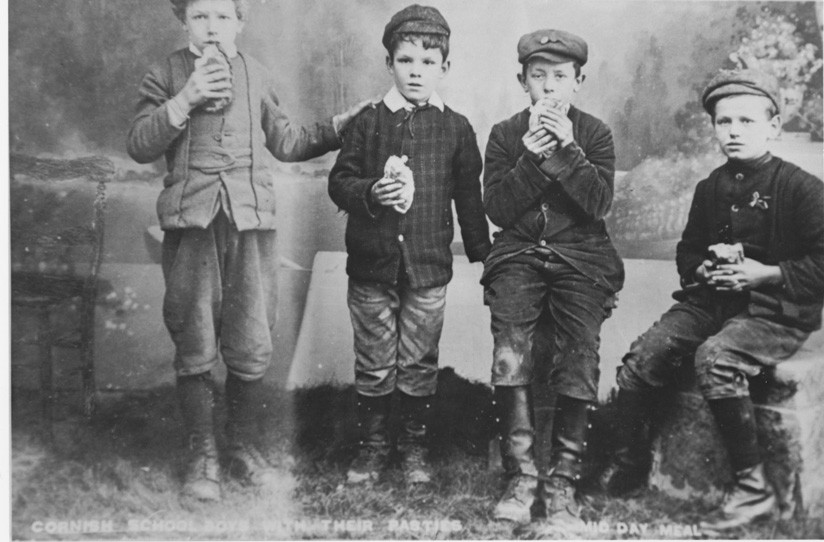

The subtleties of the pasty are therefore lost. For instance Ravasio states that the pasty was a food item consumed by ‘the hungry Cornish miner’, especially tin miners of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. This was only partly the case. Evidence from the 1840s clearly shows that taking food underground only began at the very end of the 1700s, triggered by a combination of longer cores (shifts) and deeper mines, in which in most cases the miners were seeking copper rather than tin. (See chapter 5 of my From a Cornish Study.) This suggests that there is a pre-mining history of the pasty left to uncover.

However, although not drawn out here, the precise historical context of the pasty’s material production may not be that relevant. The article draws out a few points of interest from the ‘desiderata’ of food appreciation. While the pasty was a fairly unsophisticated food with an original rustic status, its association with mining could also be read as manifesting the ingenuity of mining communities, using a pastry case to protect a hearty filling. It also means that it remains a way of expressing an identification with that lost mining past.

The norms of the pasty are intertwined with its ‘authentic’ ingredients. These tend to be potato, onion and beef, while deviations from these norms are viewed as inauthentic. In reality in the past pasties were made from whatever ingredients were at hand. Modern myths of authenticity might therefore produce rules that are far stricter than historical reality and may undermine the historical functional role of the pasty. Nonetheless, Ravasio believes that such myths are still relevant as they tell us something of a society’s changing responses to its own past production.

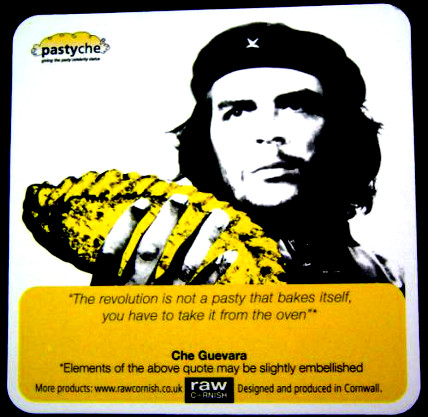

Norms are also important as they establish the boundaries between everyday and exotic food. In this way, the variety of ingredients that are now found in pasties are an example of appropriation and add a degree of exoticism to a rather basic food item.

While not telling us that much about the pasty that we didn’t know already, this article signposts a possible route to a more nuanced analysis of this food item and its changing place in Cornish culture. There’s a dissertation subject waiting here for someone. When we next eat one, are we symbolically consuming our ancestors, becoming spiritually strengthened by this ritual act? When the visitor eats one, is it with a frisson of excitement in partaking in the ‘authentic’ experience of munching a Cornish pasty in Cornwall? Does it make the consumer more ‘Cornish’? Does it prop up the Cornish identity and a sense of difference? And if so, what consequences does all this have for the Cornish people?