MikeTripp, ‘Cornish wrestling in the nineteenth century’, Sport in History 43, 2 (2023), pp. 137-165

Mike Tripp has carved out a space for himself as the leading scholar of the history of Cornish wrestling. His latest contribution is a useful summary of the rise and fall of the sport over the course of the nineteenth century, using the career of Tom Gundry, one of Cornwall’s champion wrestlers of the first half of the 1800s, as illustration.

The history of Cornish wrestling is discussed within a context of the ‘persistence of difference’, resting on Philip Payton’s peripheralisation model of the 1990s. Wrestling in Cornwall, Tripp proposes, was significantly different from the experience of sports elsewhere. By the later 1800s, those pursuits were busy organising their calendars, adopting standard pitches, fixing time limits and gate money and embracing (or futilely resisting) the march of professionalism. In contrast Cornish wrestling remained a local, more unorganised and spontaneous activity, revolving around feast days and traditional holidays.

To a large extent this difference was because it was declining from mid-century. The last tournament in London, previously along with Exeter a popular venue for Cornish wrestling, took place in 1873. Even in Cornwall, tournaments became shorter, competitors were fewer, spectators thinner on the ground while prize money was shrinking. These factors fed on themselves to create a vicious spiral of decline.

This late-century decline is ascribed squarely here to the economic difficulties that were transforming Cornwall’s mining economy, although this is also stated as the principal among ‘a number of contributory factors’. Those factors may be a little more critical than suggested as it’s noticeable that the fall in the number of tournaments and lack of prize money subscribers or competitors first appeared in the early 1860s, a few years before the first major depression in Cornish mining in 1866.

Cornish wrestling may have seemed to be a pre-modern sport, yet monetary considerations were hardly absent during its early nineteenth century heyday. Promoted especially by publicans eager to expand their takings, money prizes were favoured from the 1820s rather than the previous hats and objects of precious metal that were fought for in the eighteenth century. Tom Gundry, born in Sithney in 1818, was recorded as entering his first tournament at nearby Helston in 1835 and made an estimated minimum £270 from prize money (equal to £37,000 in 2021) before retiring in 1853.

Nonetheless, wrestling remained a sideline as Gundry continued to work as a miner, becoming a captain by the 1850s. Yet he was clearly not uninterested in the cash benefits of the sport. This is illustrated in his involvement in ‘faggoting’ or match-fixing, paying for opponents to retire or agreeing to split the prize money with them. This led to his exclusion from some tournaments in the 1840s.

Faggoting was one factor leading to the decline of Cornish wrestling in the second half of the 1800s. But the main one was mass emigration and depopulation, which removed potential competitors and spectators alike. Wrestling, like the revived Cornish language, in the twentieth century then became a symbolic icon of Cornish identity rather than being embedded in that identity as a widely practiced material activity. Indeed, surely the survival of Cornish wrestling and its mini-revival from the 1930s owed itself to the wider Cornish revival and its ‘search for difference’ rather than being a cause of that wider movement.

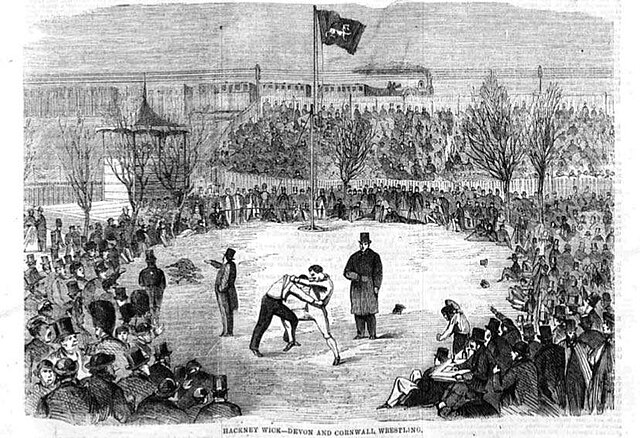

Moreover, now that Mike Tripp has laid very solid foundations for the study of Cornish wrestling, some deeper consideration of the relationship of the sport to Devonian wrestling might be of interest. As he points out, wrestlers from both Cornwall and Devon were present at the frequent London tournaments of the second quarter of the nineteenth century. These were sometimes conducted under Cornish rules and sometimes under Devon rules. The latter allowed the wearing of heavy boots and the practice of shin kicking. This contrast, both at the time and later, promoted a sense of otherness, with the altogether more civilised and skilful Cornish wrestling being contrasted with the brutal kicking of the barbaric Devonians. On the other hand, Cornish and Devonian wrestlers were clearly in close communication. And what is the significance of the fact that in 1845 when the first society for wrestlers from the south-west of Britain was established, it was for wrestlers from Cornwall and Devon, despite their differences?

(Mike Tripp’s detailed account of the sport – Cornish Wrestling: A History (2023) has been recently published by the Federation of Old Cornwall Societies)