Vera Köpsel and Cormac Walsh, ‘Coastal landscapes for whom? Adaptation challenges and landscape management in Cornwall’, Marine Policy 97 (2018), 278-286.

Anyone recently visiting Godrevy, on the coast between Camborne and Hayle, may be surprised to learn that the site has been described as the first example in Cornwall of conflict over climate change adaptation. Largely out of sight, a vigorous debate has apparently been raging for up to a decade about how to respond to the demands of climate change at Godrevy. This article uncovers that debate and sets it in context.

The main thrust of this piece, by geographers from the University of Hamburg, is that the way those involved in environmental management understand landscapes has material implications. The authors note that there’s been growing attention on the need to bring ‘lay knowledges and socio-cultural values’ into coastal management. They adopt a social constructivist perspective on landscape, noting how it’s subjectively perceived, an ‘individual and collective mental construction’ that is consequently dynamic and changeable.

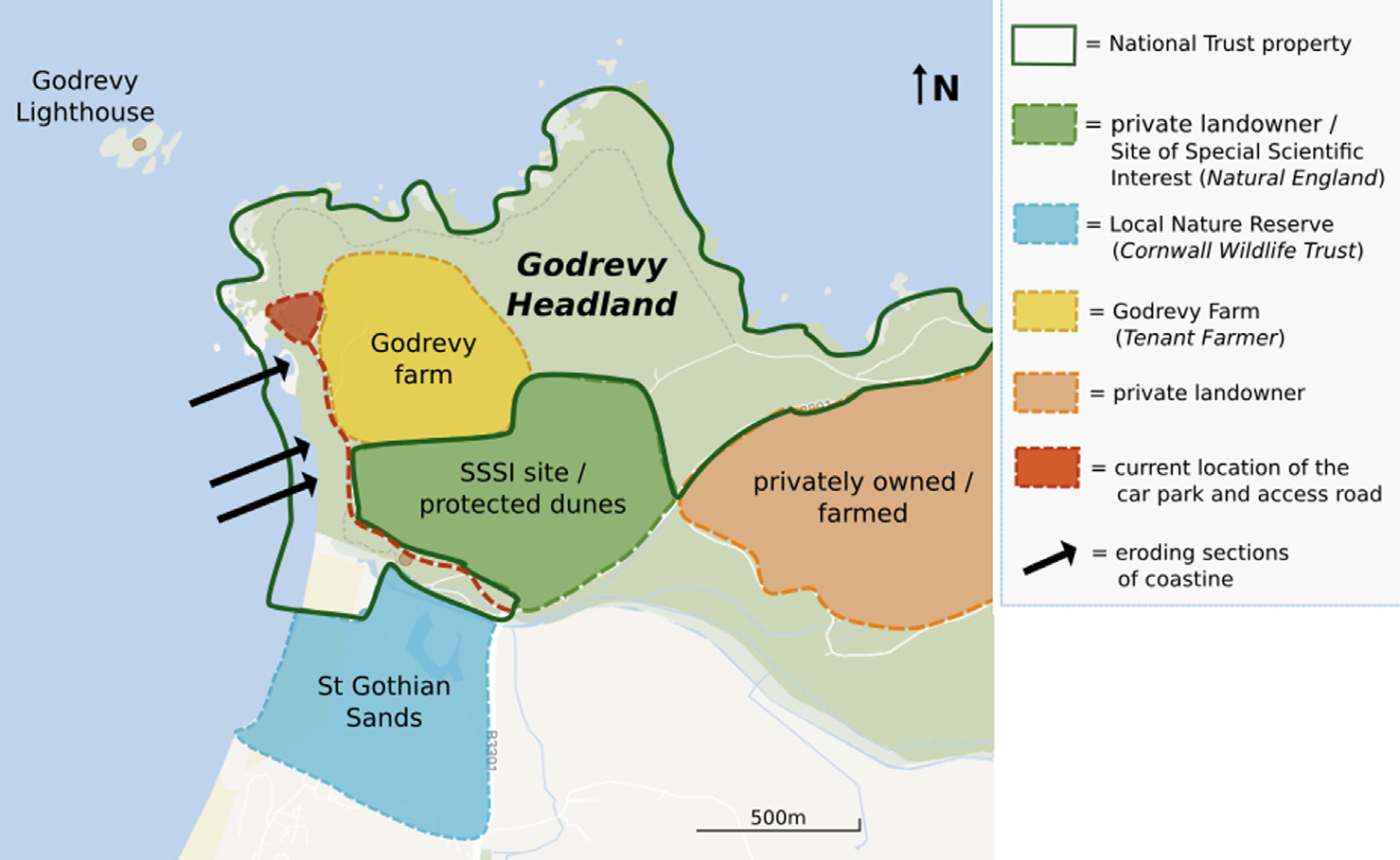

The landscape, particularly at iconic sites such as Godrevy, or the Cornish coast more generally, is a form of commons where the issue of access looms large. But competing claims of nature conservation and visitor access are bounded by complex webs of property ownership and a pluralism of management bodies. Into this mix we now have the added complication of responding to climate change.

The value of this article lies in its empirical examination of the management of Godrevy. Here, the soft sandy cliffs, facing west and regularly buffeted by storms sweeping in off the ocean, are eroding at the rate of half a metre a year. This means that the narrow road to the headland will be undercut within the next five years.

In response the National Trust (NT) has proposed moving the road inland to enable continued access to a more permanent car park near Godrevy Farm. However, this would entail breaching a Site of Special Scientific Interest and protected duneland. Fortunately, the NT has not been able to proceed regardless as it doesn’t own all the land and has to negotiate with other interested bodies. These include AONB partnerships, Natural England, the Cornwall Wildlife Trust, the Towans Partnership, the Cornwall Seal Group, the local parish council and businesses.

After conducting interviews, Kopsel and Walsh identify two main narratives of Cornwall’s landscape among these various ‘stakeholders’. The first, strongly adhered to by the NT and businesses, constructs the landscape as the result of human-environment interaction. This is a fundamentally anthropocentric perspective where the landscape is managed for people. Its important features include the natural elements (dunes which are home to rare species and wildlife, including one of Britain’s main grey seal colonies). But it also encompasses the lighthouse, café and paths. The significance of Godrevy for the NT is as a ‘visitor destination … for locals and tourists’ and the primary goal is seen as enabling access while preserving its beauty. The inconvenient contradiction between these is brushed under the carpet. As the authors note, such an open access policy ‘clearly poses challenges to the site’s natural environment’. Although it might be added that the monopoly over car parking adds considerably to the Trust’s bank balance.

The NT’s narrative is opposed by another that views the landscape principally as a natural system and a sensitive wildlife habitat in need of protection. The researchers found that this view was held by the Cornwall Wildlife Trust, Natural England (with reservations) and most strongly by the Towans Partnership. While the NT saw the imminent closure of the cliff road as a potential disaster the others to varying degrees regarded it as providing a welcome control over the spiralling harmful impact on wildlife habitats posed by people and their dogs.

The article is a useful reminder of the way in which professional knowledges (often presented as neutral, technical or value-free) are informed by socio-cultural values and how these values have real world implications. However, it offers no easy answer to negotiating between these differing values. Moreover, it says little about the other more material factors that help to explain these perspectives. For example, the NT’s monopoly over vehicle access adds considerably to the Trust’s bank balance. Comments from Natural England about the contribution visitors make to the local economy also reflect the influence of government economic policy on that quango.

From a Cornish Studies perspective it’s interesting to note how the majority of ‘stakeholders’ in this debate are quangos or private bodies operating well out of the public gaze. It’s revealing how little of the ‘debate’ appears to have emerged into the public domain, but is conducted behind closed doors by a group of self-appointed ‘stakeholders’, the majority of whom, one might suspect, are not indigenous.

An explicitly Cornish perspective on the landscape at Godrevy, one which views it as neither a playground for people nor solely a wildlife habitat but also as part of our Cornish heritage, seems to be missing, or wasn’t invited. But such a perspective might put the issue of adapting to climate change at this site in a somewhat wider context. As anyone who has visited Godrevy in summer, or at other times of the year for that matter, can attest, there’s growing congestion, overcrowding and littering at the site. This situation has been directly encouraged by the NT’s ‘open access’ strategy, coupled with its desire to maximise income from car parking. It might therefore note that Godrevy also offers one of the more blatant examples in Cornwall of capacity limits being reached and breached.

A Cornish Studies perspective would surely recognise the fundamental unsustainability of regarding the Cornish coast merely as a playground for infinite numbers of visitors and a cash cow for the NT. To protect both the sensitive wildlife habitats and the Cornishness of this landscape, visitor numbers have to be controlled and the NT brought under local control or dissolved. This should be part of a wider policy to cap and then reduce the pressure of tourist numbers through a tourist tax and other measures. That would have the added advantage of reducing carbon emissions and thus help in a small way to tackle the root cause of the unfolding climate emergency.

In short, leave the coast to the seals. It’ll be in better hands. (Or flippers.)

I am a ‘local’ (Camborne!), who has grown up with Godrevy. I’m also a NT member. However, I get increasingly angry with the state of things at Godrevy. Too many cars and ever-spreading car parks, too many tourists, not enough appreciation of the site’s importance, and a general slide towards a kiss-me-quick, ice-cream-licking approach to visitors.

I feel any car park needs to be back near the entrance to the site. The coast road is, seemingly, going to disappear anyway, and the headland should be free of cars. It’s rather like Mont St Michel, where the removal of the cars at the base of the island has returned the view to the original.

My feeling about the NT is that it is totally bureaucratic and plays with ‘places’ and ‘visitor numbers’ without looking at the context. They seem uninterested in localities – best seen through the gift shops which sell the same mass-produced tat wherever you are from Salisbury to Trelissick.

The AONB etc must take the lead in this, but there must also be a place for our heritage organisations. More importantly, this must happen quickly, while there is something left to save.

LikeLiked by 1 person