Douglas Brown and Steven Wrathmall, ‘Geographical modelling of language decline’, Royal Society Open Science 10 (2023): 221045 (online at https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.221045)

Statistical modelling has been used to predict traffic flows, stock market fluctuations and opinion polls among other things. Here, two physicists at Durham University have applied it to the geography of culture change, using the Cornish and Welsh languages as illustration. Apart from some work modelling the boundaries of English dialects the authors claim that this is the first attempt to model the historical geography of a language.

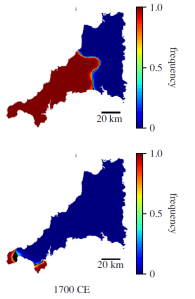

I won’t pretend to understand the details of the maths underlying their model. Suffice it to say that it’s a complex differential equation using finite difference method. The basic factors included in the model are population distribution and density, interaction of the population over time, competition with English and the pressure to conform to the dominant language. Given these, the model aims to predict the course of language change over time and compare it with what actually happened. In the case of Cornish, a starting point is assumed when the language was spoken up to the Rivers Tamar and Ottery and its spatial decline is then modelled to an end point around 1800, when it disappeared in a puff of curses from Dolly Pentreath.

Interestingly, the modellers found that with no bias against Cornish, or pressure to conform, according to their model the language boundary should have remained well to the east of Bodmin as late as 1700, instead of by then being pushed to the margins of the Lizard and West Penwith. As bias against Cornish is increased in the model the historical geography comes to resemble – broadly – what is thought to have actually happened.

The authors conclude that their model could be used more widely to predict vulnerability to language decline in any particular district (or any culture change than can be mapped come to that), although only in the absence of regular movement between population centres. Moreover, they reach the intriguing conclusion that the geography of Cornwall may have played ‘a greater role than is typically imagined’, greater that is than transient political events such as the Reformation or the 1549 rising. They also intruigingly suggest that Cornish was ‘already at a geographical disadvantage’ given the topography of its territory.

Of course, like any model, credibility depends on its inputs. Some of the assumptions made here are questionable, to say the least. For example, the modern population distribution is assumed to be a proxy for the past. Yet, by the end point of 1800, west Cornwall had been in the throes of industrialisation for almost a century. A population distribution skewed towards the east in the middle ages was already well on the way to being reversed and skewed to the west.

Moreover, the sources used for the real decline of the language are limited to M.J.Ball’s 1993 edition of The Celtic Languages and Ken George’s speculations about the number of Cornish speakers over time published in 1986. More recent discussions of the historical geography of Cornish, for example Matthew Sprigg’s work of 2003 (Cornish Studies 11) or Oliver Padel’s discussion of where middle Cornish was spoken have been ignored.

Ken George’s work is seriously flawed in at least three ways. First, there is an assumption that the boundary between Cornish and English-speaking areas steadily moved westwards over time. This misses the now generally recognised stability from around 1300 to 1500 that produced the clear isogloss running from the Camel estuary south to Fowey.

Second, the population estimates employed in Ken’s article were based on guesswork from the 1950s and 60s and took no account of more recent demographic studies. The estimates for 1086 and 1377 are in particular far too low. As the authors of this article admit, it is ‘possible that the population estimates are inaccurate, but it is not the place of this work to speculate on such’.

Finally, both George and Brown and Wrathmall in this piece assume a discrete boundary between two language zones whereas in reality there could well have been islands of English-speakers in the towns and trading ports of the west and islands of Cornish speakers in remoter, rural parishes in the east.

… not to mention bilingual zones where social, economic, political, and legal pressures would change the dynamics of diglossia and code-switching, thus precipitating language shift.

LikeLike

I think I agree with Timothy Saunders, though I don’t know what some of his long words mean. I think it’s self evident that society is not homogenous. Therefore I speculate that language change within society is not homogenous and will be affected by the functional requirements of communication at every level.

LikeLike