Joanie Willett, ‘Counter-urbanisation and a politics of place: A coastal community in Cornwall and rural gentrification’, Habitat International 141 (2023)

It is rare to find an academic article that sets out (and succeeds) in joining the dots between three processes: economic policy, gentrification and counter-urbanisation. This one does. Joanie Willett discusses the impact of counter-urbanisation on a coastal village in west Cornwall (anonymised as ‘Porthurst’) and asks how it has created a ‘new politics of place’.

The concept of counter-urbanisation is usually applied to the movement of better-off and more educated migrants to peripheral areas in search of a better quality of life. It gathered pace in the 1960s and has continued into the 21st century. As long ago as the 1980s, the late Ron Perry provided an incisive and critical analysis of the effect of it on Cornwall and its culture. As Ron noted, Cornwall was not changing the in-migrants; in-migrants were changing Cornwall.

Academic interest in counter-urbanisation receded after the first wave of migrations peaked in the 1980s, but policy-makers in Cornwall had by then eagerly seized on the migratory movement and further encouraged it. Counter-urbanisation was legitimised by a raft of economic theories that looked to ‘neo-endogenous growth’, basically importing knowledge and innovation to kickstart what they viewed as undynamic and backward rural areas.

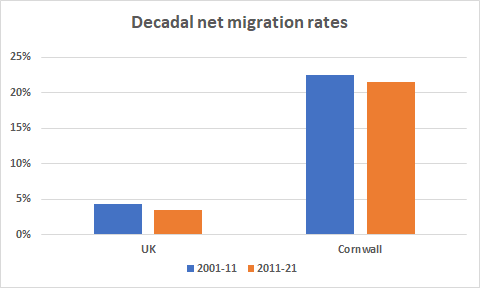

As a result, in-migration to Cornwall has relentlessly rolled on and in the new century was reinforced by various theories around the knowledge economy and creative industries, all being premised on further ‘people-led growth’. Except that the promised ‘growth’ for the existing population never properly materialised. While the population total steadily rose, chronic economic problems remained. Moreover, new ones appeared such as a growing housing crisis in the 2010s and the increasingly visible environmental damage caused by the housing and road-building required to ‘accommodate’ the desired new population.

In short, as Ron Perry pointed out 40 years ago, the myth of the dynamic migrant is exactly that – a groundless myth propagated most energetically by in-migrants occupying key strategic posts with an inflated sense of their own worth. Meanwhile, as Joanie Willett reports, there is no evidence of knowledge and skills ‘spilling over’ to improve the lives of non-migrants. Instead, newer forms of exploitation and displacement have emerged.

As counter-urbanisation becomes ‘more embedded and more entrenched’, non-migrants are increasingly priced out of housing markets and have to leave – a ‘structural displacement’ of locals from tourism economies dominated by ‘visitor imaginaries’. For Joanie Willett, these ‘imaginaries’ invoke ‘sleepy narratives’ at odds with the complex and rich historical culture of Cornish localities. But such narratives are not just culturally demeaning, disempowering local heritages. The conclusion here is that they bring undesirable consequences for liveability.

Economic policies that encourage population growth are linked to the housing crisis through the process of gentrification. First applied to urban areas, this sees an affluent, post-industrial and middle class, in-migrating population, sometimes spearheaded by artistic communities, colonising run-down and poorer locations. Their demand for housing and greater access to resources results in the displacement of the local working class through rising housing costs. In Cornwall this process is exacerbated by the expropriation of housing stock for use as second homes or holiday lets.

This presents a challenge for those trying to maintain a cohesive village community. In ‘Porthurst’ shared spaces in institutions such as the gig club or local history outings play a role in introducing in-migrants to the ‘back-stories’ of the place. Nonetheless, this is in constant tension, given the difficulties faced by locals in maintaining their links with the village.

Joanie Willett ends by posing a policy question. Are policy-makers trying to improve places or the lives of people living in places? Current reliance on stale and half-century old policies of encouraging population growth have clearly failed to make the lives of non-migrants more secure, as this article clearly demonstrates. It also perversely, given the ‘back-to-nature’ lifestyles assiduously marketed to incomers, threatens local environments and landscapes through the large-scale housing schemes designed to attract ever more migrants.

We now need to build on scholarship such as this that identifies, describes and contemplates the ‘complex assemblages’ at work in places like ‘Porthurst’. Hopefully, this will trigger a broader analysis of the set of power relations that enable this ‘assemblage’ to operate. What institutions reproduce the ‘assemblage’? Who benefits from never-ending population growth? Only then might we be able to envision alternatives and devise the options – in economic policy, housing and devolution – that could create a different and better future for Cornwall.