Anke Winchenbach, Paul Hanna and Graham Miller, ‘Constructing identity in marine tourism diversification’, Annals of Tourism Research 95 (2022)

Anyone who has watched Mark Jenkin’s acclaimed film Bait will be familiar with one of its central plot themes. This revolves around the tension between a man stubbornly clinging to making a living as a fisherman (even without a boat) and his brother who has turned to taking tourists on trips along the coast.

While the number of inshore fishermen has sharply declined since the mid-twentieth century, there has a been a rise in the number offering sightseeing trips or recreational fishing, sometimes combining that with traditional fishing in the winter months. Policy-makers have touted tourism as a magic bullet that can pitch declining coastal communities headlong into a virtuous circle of growth. At the same time, most studies of marine tourism diversification have concentrated on its economic impact rather than the sociocultural effects. But how do those making the transition from what is seen as a traditional way of life with its autonomy rooted deep in a community heritage experience this shift?

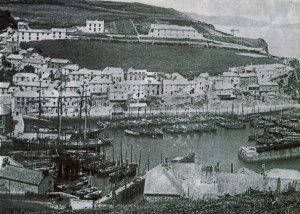

This article sets out to answer that question by analysing the narratives of seven men who have made the change from fisherman to tourist operator, based in communities from Cawsand to St Ives by way of Mevagissey. Winchenbach et al. adopt a phenomenological and qualitative approach to the issue. This focuses on the psychosocial responses of the men concerned and their individual occupational, gendered and personal identities rather than the impact of marine tourism diversification on collective identity.

It perhaps comes as little surprise that the men’s experiences vary and are ‘dynamic, complex, multifaceted and embedded in social encounters’. Four themes are used to elucidate this. The first is their physical and mental health. Some report less pressure and better mental health although one or two express regret at the change. The second is their interaction with the customers. For some this was enjoyable and ‘fun’; for others, used to the solitude of small boat fishing, it was a source of conflict. Third, the importance of family, community and local business support for their new ventures was identified as critical in the transition. Finally, the men could at times struggle to construct a new hybrid sense of identity to replace the masculine, producer-based culture of fishing.

The authors rightly reject overdrawn binary understandings of producer as opposed to service orientated identities and insist that the psychosocial aspect of switching from fisherman to tourist operator can be negotiated successfully, as the majority of their respondents would appear to indicate. Moreover, they call on policy-makers to move beyond economic narratives and consider the ‘psychosocial and relational aspects’ when urging fishermen to abandon their traditional way of life to embrace marine tourism.

This is no doubt a salutary suggestion but the wider picture might suggest that transitioning from fishing to tourism, or from over-fishing to over-tourism, is no long-term panacea for Cornish coastal communities blighted by second home ownership and gentrification. Indeed, it may make things worse. In addition, as individuals recalibrate their personal identities, collective identities may be hollowed out, fragmented and ultimately discarded. In reality, the magic bullet of tourism, proposed as such as long ago as Q’s short-lived Cornish Magazine of 1899-1900, has turned out to be a bullet aimed squarely at the heart of Cornwall and Cornishness.