Joanie Willett, ‘Place-based rural development: A role for complex adaptive region assemblages?’, Journal of Rural Studies 97 (2023), pp. 583-590

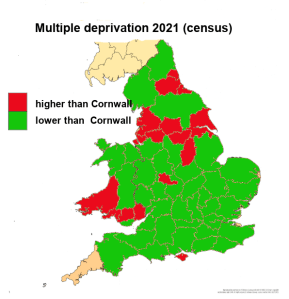

Since Cornwall received the highest level of EU funding in the early 2000s it’s been clear that a considerable gap exists between the perceptions of policy-making elites and the public. While the former wax lyrical about the creative industries, digital tech, aerospace, marine energy, higher education and advanced engineering that are supposedly transforming opportunities, the latter bemoan the loss of Cornwall’s traditional industries of farming, fishing and mining and grumble about an imagined dependence on tourism alone.

Joanie Willett set out in her research for this article to ask what regional economies look like ‘from the position of local inhabitants’ in Cornwall and south-west Wisconsin, with a view to how to bridge the gap between those ‘left behind’ and those who think they’re in control of the growth juggernaut. To do so, she interviewed 25 people in each location, mainly members of the public, to discuss the ‘tangled threads’ of their stories about their regional economies.

The conclusion is that, in order to reduce the sense of frustration and lack of control in the face of the intensifying ‘precariarity’ being experienced by many, the ‘multiple broken connections between participants and local economies’ need to be addressed and re-forged. If these spaces can be re-connected then those struggling with their everyday lives might be plugged back into ‘the constellation of knowledges of the assemblages of which you [sic] would like to be part’ and inequalities might hopefully be reduced. This would allow the regional economies to work ‘more effectively’.

The economy is viewed here not as a fixed set of structures and objects but as an organism, constantly mutating and evolving. This organism is part of a ‘complex adaptive region assemblage’ which provides the theoretical basis for the examination of popular narratives. Assemblage theory can be traced back to the writings of the French political philosopher Gilles Deleuze in the 1980s. However, it has become a fashionable concept across the social sciences since the 2000s, a bit like the risk society or the knowledge economy did. Society is seen as a collection of assemblages at varying scales. These networks and clusters connect and overlap with elements that fit together but that can be detached and re-attached and relate through contingency rather than necessity.

Metaphors such as mobility, fluidity and mutation are central to assemblage theory but, as some have pointed out, bring with them problems of vagueness and indeterminacy, the language suggestive and elusive rather than precise and analytical. It could also be read merely as a way of saying that everything is connected but also complicated. Moreover, if everything exists within assemblages and contingency (or chance) is so critical then the term is in danger of becoming just descriptive rather than in any way explanatory.

Although somewhat obscure, to say the least, Deleuze did have a few things to say about political power, but that aspect is often lost from the latest iterations of assemblage theory. The regional economy, we are told here, needs to work ‘more effectively’ and can ‘flourish’ through the adaptation of regional actors to ‘new growth paths’. However, do growth paths, whether new or old, not need radical re-assessment in the light of the more existential global threats posed by late capitalism? In the light of this, is the improvement of information flows the best we can hope to achieve? Meanwhile, the older question of in whose interests the regional economy operates might still have some resonance and be worth posing at some point.