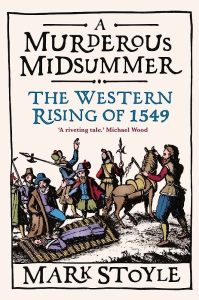

Mark Stoyle, A Murderous Midsummer: The Western Rising of 1549, Yale University Press, 2022

Mark Stoyle has established himself as the leading expert on the rising that took place in Cornwall and Devon over the summer of 1549. This is generally known as the Western Rising, although some Cornish nationalists have preferred the description the Prayer Book War. Based on many years of fine-grained work in the archives, the book brings together Stoyle’s recent series of articles on the rising and expands on them.1 The result is a fluent, compelling and thought-provoking re-telling which is likely to become the standard work on the subject for many years to come. A Murderous Midsummer has three parts, dealing with the background to the rising, including the serious Cornish commotion of 1548, the course of the rising and finally its aftermath, when attention turned to a factional struggle at the heart of government in London.

Mark Stoyle’s painstaking research allows him to revise the story of the rising while also reinforcing some traditional continuities of interpretation. Or sometimes both. For example, he concludes that the number of priests who were killed or executed during the rising was much higher than was previously thought. This reinforces the account of the rising first put forward more than a century ago by Frances Rose-Troup in 1913. She argued that the primary trigger was religious change associated with the Protestant Reformation. Mark Stoyle confirms this reading, suggesting that doctrinal disputes in Devon produced circumstances ripe for a rising on the introduction of the new Prayer Book. In west Cornwall religious change was exacerbated by the replacement of Latin in church services by English. In contrast to some recent accounts therefore, he plays down the role of social protest or anti-landlordism in the conflicts.

Perhaps the most significant revision offered in the book revolves around the timing of the Cornish part of the rising. Historians have hitherto accepted at face value an earlier account that the Cornish began to gather at Bodmin on June 6th, four days before a rising took place in the mid-Devon parish of Sampford Courtenay. Stoyle convincingly repeats the point he first made in his 2014 article that the date of the Cornish rising could not have been that early and was in fact July 6th, a month later. The ‘true begetters’ of the rising were Devon yeomen and not Cornish insurrectionists.

This has implications for our broader understanding of the rising. In the past, historians have commented on the tardiness of the Cornish, who apparently took seven weeks to arrive and join up with the Devonians. That gave time for the Government force under Lord John Russell to be reinforced. By the time the Cornish appeared on the scene the odds were becoming heavily stacked against the insurgents. Yet in fact the Cornish had been the opposite of tardy. They had found their leaders, gathered an impressive force together, neutralised potential opposition within Cornwall and marched the 60 or so miles from Bodmin to Exeter and all in the space of just three weeks. There were also significant differences between the protestors from Cornwall and Devon. The Cornishmen were led by more socially exalted men in Humphrey Arundell and John Winslade, whereas the Devonian leaders were relatively anonymous yeomen, respected propertied men in their village communities but with little weight beyond. It was the arrival of Arundell, Winslade and the Cornish host that gave the rising more focus and made it more of a danger.

Mark Stoyle claims that the Western Rising was indeed much more of a threat to the reforming Protestant rulers of the time than it’s usually seen to be. It had a serious political programme, some leaders with important connections and a clear objective. The Cornish especially expressed their intention to head east and take their case directly to London in a re-run of the 1497 rising. That was not to happen after the defeat by Russell at the battle of Fenny Bridges to the east of Exeter. Nonetheless, Stoyle makes a convincing counter-factual case that the rising was not bound to fail. In early July the Government’s forces were still weak and Russell was dithering over whether or not to retreat back into Dorset. Had he done so Exeter might have fallen. Moreover, had the Cornish arrived a week or so earlier or had the Government’s reinforcements been delayed, the rising could have had a very different outcome.

In addition to revising the timing and the precise role of its Cornish and Devonian components, the other new light shone by this book concerns the factional struggles that followed in London during and after the trial of some of the participants. Mark Stoyle expands on the idea that the leading Cornish recusant family of the Arundells of Lanherne was deeply implicated. The brothers Sir John and Sir Thomas Arundell were arrested and imprisoned in the Tower in 1550 and Stoyle suggests that this was the result of confessions from some of the condemned rebels. Sir John (who was released in 1552) and Sir Thomas (beheaded that same year) were very possibly in active communication with the leaders of the rising and ’may have attempted to guide, to channel and otherwise to exploit the Western Rising as part of a game played for the highest politico-religious stakes’ (p.296).

It seems rather churlish to raise any caveats about what is likely to become the standard work on the causes, course and consequences of the Western Rising of 1549. However, as befits what is essentially a political and religious history there are only fleeting references to the socio-economic context of the risings of 1548/49. While an explanation based on social protest over agrarian change and anti-landlord sentiment is probably correctly rejected there’s little mention of the specific social background to the risings. They occurred against a background of price inflation and just after a serious outbreak of plague and a mortality crisis in 1547 when in Cornwall as many as 10-15 per cent of the population may have perished. Perhaps the recurrence of the plague, coinciding with economic problems and changes in traditional religion imposed by a distant government in London, ensured that people, whether in Devon or Cornwall, felt they had little to lose in rising in angry resistance and taking up arms.

- ”Fullye bente to fighte oute the matter: Reconsidering Cornwall’s role in the Western Rebellion of 1549′, English Historical Review 129, 538 (2014), 549-77; ‘Kill all the gentlemen?: (Mis)representing the western rebels of 1549’, Historical Research 92, 255 (2019), 50-72; ‘The execution of rebel priests in the Western Rising of 1549, Journal of Ecclesiastical History 71, 4 (2020), 755-77. ↩︎

Very interesting

LikeLike