Most modern employment classifications treat mining and quarrying as a single economic sector. So how many more workers did clay extraction and quarrying add to the mining and quarrying sector in 1861? The answer is not that many when compared with the dominant mining for copper, tin, lead and other minerals.

While metal mines accounted for 30 per cent of adult male workers in 1861, quarrying added a maximum of 1.8 per cent and the china clay industry another 1.1 per cent. Nonetheless, this means that almost a third of Cornwall’s men in the early 1860s were directly engaged in working the natural underground resources of the region. There would have been many others who were indirectly dependent on this sector, something that would have dire consequences when mining began to contract in importance.

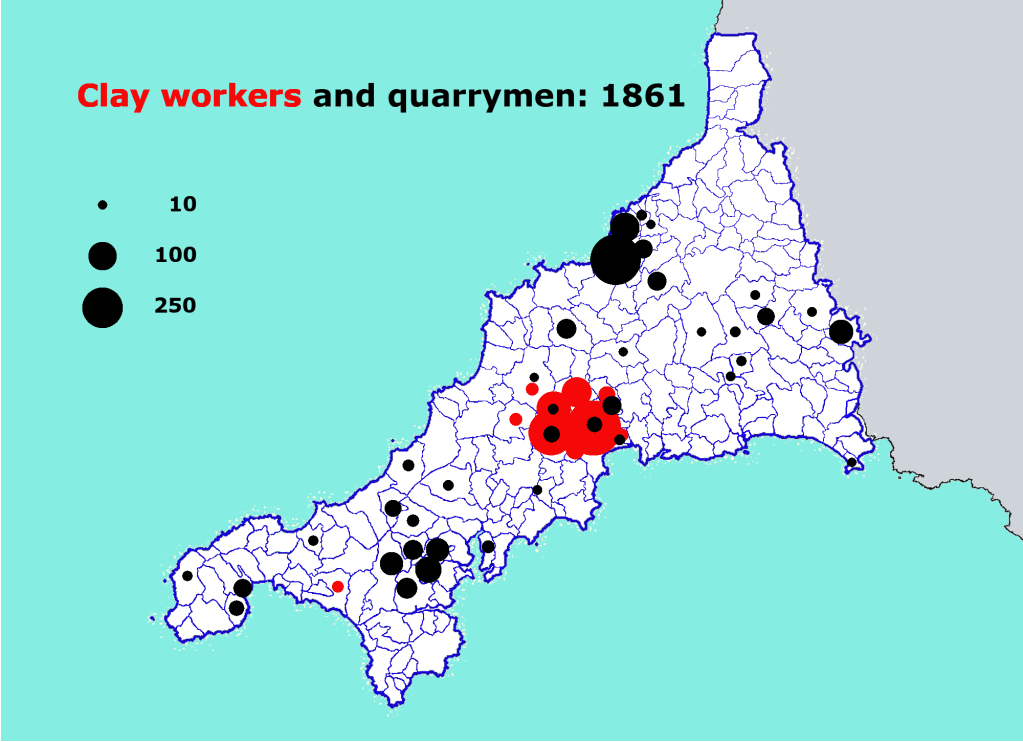

China clay was still in its infancy in the early 1860s, although it was growing fast and was destined to take over from mining as the main industrial pursuit in mid-Cornwall well before the end of the century. As the map above shows, this was an extremely concentrated business, focused almost entirely on the St Austell district in mid-Cornwall.

Quarrying on the other hand was more widely distributed. While there were 91 parishes in 1861 each with ten or more metal miners, there were just ten with ten clay workers or more but 38 with more than this number of quarrymen. The two principal quarrying districts – St Teath and Tintagel for slate and the eastern part of Carnmenellis near Penryn for granite – can clearly be identified from the map.