Or should we say a woman’s work is never properly quantified? Putting aside the difficulty involved in differentiating (if indeed we should) between paid and unpaid work, the nineteenth century census returns are anything but consistent in their treatment of women’s occupations. However, if we take the descriptions in the census at face value, we find that in Cornwall (as in most other parts of the British Isles with the possible exception of textile districts) domestic service employed the greatest number of unmarried women between the ages of 15 and 69.

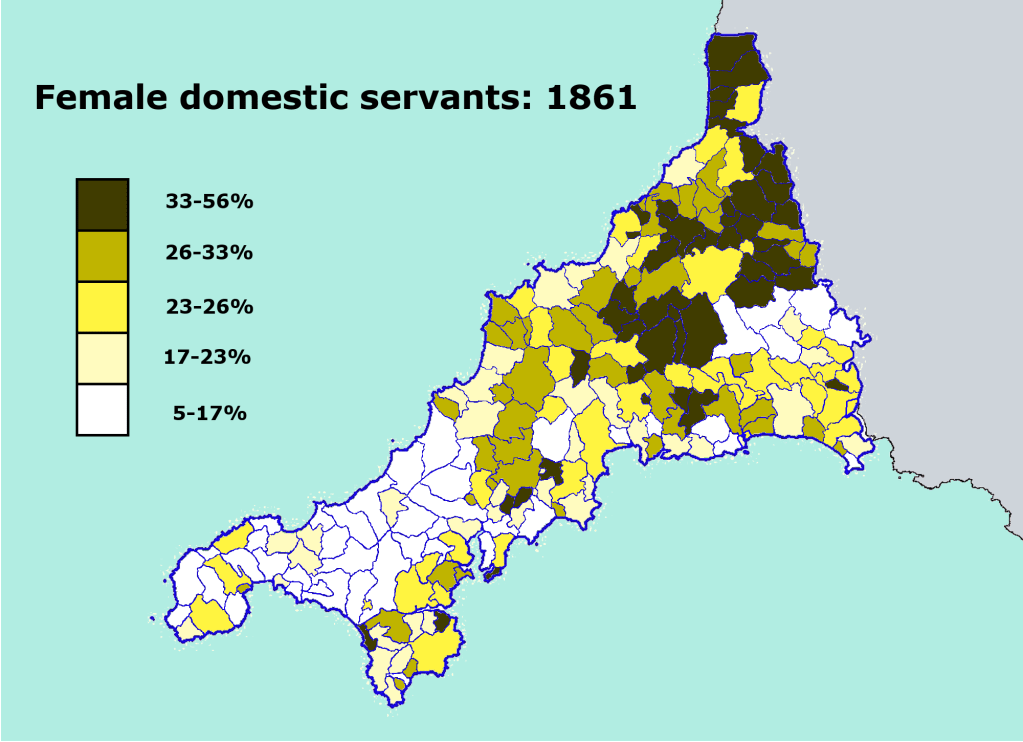

If the number of those described as domestic servants, house servants, general servants, housekeepers whose status was explicitly servant, ladies’ maids, child’s maids, parlourmaids, laundrymaids and similar are totted up, we find that 21 per cent of unmarried women were described as such. The map below suggests a clear pattern to this, with more servants in the north of Cornwall and fewer in the west. Meanwhile, towns were home to noticeably more domestics than their surrounding hinterlands.

So far so clear. But the boundary between servants and other occupations was permeable. For instance, do we count someone described as a grocer’s servant as a servant or as engaged in retail trade? (I’ve opted for the latter but this is a subjective decision). What about chambermaids in hotels or inns?

The descriptor ‘farm servant’ presents the most difficulty. For the purposes of this classification exercise I distinguished between these and domestic servants on the grounds that some farm servants may have been heavily engaged in farm work such as feeding animals, tending poultry, collecting eggs, milking cows or even field labour, which would make their lot substantially different from that of a domestic servant in an urban middle-class household.

Moreover, enumerators were obviously also inconsistent in recording farm servants, no doubt including many as domestic, house or general servants. Wild fluctuations from parish to parish in the number of servants would seem to confirm this. For example, 24 per cent of unmarried women in St Gennys parish in the far north of Cornwall were described as farmers or farm servants or agricultural labourers, whereas in neighbouring Jacobstow that proportion was just four per cent. Such a gap seems too large to be credible.

Very interesting. So is it possible that a factor influencing the different % share could be alternative better paid jobs in mining areas whereas in farm based parishes there were fewer opportunities?

LikeLike

Yes, my hypothesis would be that the proportion of unmarried women with an occupational descriptor in mining districts would be higher than non-mining but I would need to return to the data again to test that.

LikeLike