Nigel Saul, ‘The Carminows and their arms: History, heraldry and myth in late medieval and early modern Cornwall’, English Historical Review CXXXVI, 583 ,2021, pp. 1419-1449

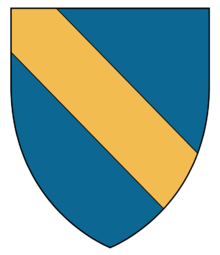

We’re told that In the fourteenth century Ralph Carminow’s right to use his family’s coat of arms was challenged by Lord Scrope, a Yorkshire landowner who happened to use the same heraldic device. The court case lost, the Carminows, in an apparent reference to it, added to their arms a Cornish motto – cala rag whethlow (a straw for tales). However, this never happened. The story was invented by the Carminows in the late 1500s.

The kernel of truth in their tale is the reverse. The Carminows were never the defendant in such a case. In reality, Thomas Carminow challenged the right of Lord Scrope to use the same coat of arms when on campaign with Edward III in France in 1360. Far from losing the challenge, both Carminows and Scrope were deemed to be equally entitled to use their coats of arms. In this article Nigel Saul indulges in some neat historical detective work to trace Thomas Carminow’s successful claim in 1360 and then explain the family’s later re-writing of this incident in the late 1500s.

The challenge while on campaign illustrated ‘sheer boldness’ on the part of the young Thomas Carminow, who backed up his case with references to King Arthur and Cornwall’s former status as a kingdom, a ‘big country’ not to be confused with mere English counties. Saul admits that the ‘view that Cornwall was a land apart, with its own geographical and historical identity’ was widespread among Cornwall’s gentry in the fourteenth century.

The final part of the article places the Carminows’ re-writing of the earlier incident in context. In the century after 1550 the gentry more generally turned to the history of their lineages, anxious to buttress their status in changing times. No doubt correctly, Saul concludes that the Carminow family myth was the result of the family’s own changing circumstances rather than a more general sense of victimisation or erosion of Cornish identity. The Carminows were painfully aware that they had been left behind by the shake-up of landownership following the dissolution of the monasteries and sale of church lands in the mid-1500s. Other families – the Rashleighs, Eliots, Prideaux and Grenvilles for example – had benefitted but the Carminows lacked the necessary connections and lost out. The re-worked story was therefore a response to the ‘family’s own appreciation of relative decline’.

Had it stopped there, this would have been an interesting if somewhat marginal piece of local and family history, shedding light on the problems of some Cornish gentry. However, Saul ends by claiming the Carminow story also adds to debates about the ‘cultural and political integration of Cornwall into the wider nation’ and to ‘trends in Cornish historiography’. While sparse evidence of those mysterious debates is presented, he suggests that the ‘insecurities … felt by Cornwall’s gentry’ in the early modern period were part of a ‘culture that was found across England as a whole’. This then somehow proves that arguments that involve ethnicity to account for Cornish identity more widely are untenable.

Despite claims to be a kingdom with Arthurian associations in the fourteenth century Cornish identity had by the late sixteenth century declined to become just a run of the mill ‘county identity’. Viewed through the lens of English history, it might look the same in form. But a deeper look reveals a very different substance, as the first two thirds of Saul’s own article imply.

The suggestion that Cornish identity was just another example of the emerging county identities found across England is questionable to say the least. How many county identities made reference to an Arthurian legacy and Cornwall’s status as a kingdom, as Thomas Carminow did in 1360? How many were adopting mottoes in a Brittonic language as late as the seventeenth century? it seems curious that the traumas of the mid-1500s and the Prayer Book Rising, which swept into its ranks a few other Cornish lesser gentry, gets little coverage in this article. Moreover, the significance of the Carminows’ Cornish language motto is not explored.

As a study of a declining Cornish gentry family in the sixteenth century this is a useful addition to the literature but claims to contribute to debates about ‘trends in Cornish historiography’ are a trifle overblown. The Carminows may have been typical of the declining smaller gentry but tell us little of the population in general. Firmly embedded in the conservative, anglocentric stable of history, this is merely another belated effort, in Mark Stoyle’s memorable phrase, to ‘thrust the historiography of early modern Cornwall firmly back into the box labelled ’English local history’, and to nail down the lid.’

Postscript: The county index for this article is disturbingly high at 44 references to Cornwall as a ‘county’ in just 31 pages.

Cornish language mottos and Cornish language canting arms were quite common in the period. I suppose I’ll get around to writing a book on it eventually.

The Carminow family died out in the main line, the Arundells of Lanherne eventually inheriting Carminow itself. A junior branch was settled in Lanhydrock parish, and they took a mark of difference on their coat of arms to distinguish it from the main line.

LikeLike