Tanya Krzywinska and Ruth Heholt, Gothic Kernow: Cornwall as Strange Fiction, Anthem Press, 2022

Towards the end of the twentieth century literary critics took a renewed interest in Gothic literature. The Gothic was soon being discovered not just in obvious horror stories such as Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (1818) or Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1898) but lurking, often unseen, in many texts. Indeed, the Gothic soon shouldered the Romantic genre out of the way and by the 2010s had become the preferred mode through which literary criticism was dissecting various cultural products.

The content of Gothic novels is both exciting and disturbing; it tantalizes while it terrifies, attracts yet repels. For example, Cornwall can be viewed from the Gothic as dark and threatening but at the same time sublime and magical, simultaneously repulsing and attracting the observer. The existence of this dual aspect is central to Gothic Studies, which involves the study of the Gothic in literature and other fields. In this book it’s what Krzywinska and Heholt call ‘doubling’, the presence of apparent contradictions in the same object. In addition to a critical approach to this core of the Gothic, Gothic concerns include ‘otherness, animism [the idea that nature and the landscape possess sentience and agency] and the sublime’ (p.10).

However, the Gothic can also at times seem elusive and Gothic Studies come in many different and seemingly multiplying strands. One of these is the regional Gothic, studies that focus on Gothic literature and other cultural artefacts in particular regions. In 1998 Avril Horner and Sue Zlosnik coined the term ‘Cornish Gothic’ as one instance of the regional Gothic. Nonetheless, according to Krzywinska and Heholt in this short but intriguing study, Cornwall has been marginalised within Gothic Studies, its centrality and special relationship with the Gothic unrecognised and unconsidered. They set out to remedy this by inserting the Cornish Gothic into Gothic Studies more generally, showing how Cornwall has served the Gothic both as a melodramatic inspiration for Gothic practitioners and as a location for ‘dark desire’. Cornwall’s marginality has meant that it played and plays a leading role in Gothic representations and its ‘rural Gothic is more cogent than ever’ in the face of the climate crisis and fears over the very future of humanity as a species.

These are large claims, but the authors succeed in illuminating Cornwall’s central place in Gothic Studies. They argue that Cornwall’s imagined landscape, ‘wild, romantic, untameable, beautiful and dark’ has provided the perfect setting for Gothic writers and artists. Moreover, this imagining has blended with an ‘evocative and creatively generated separatism’ (p.4) within Cornwall which played an instrumental part in helping to construct Cornwall as liminal and indeterminate, of England but not of England, foreign yet safely domestic, other but also familiar. In addition, Cornwall’s material past – the loss of the Cornish language, the emigration of the nineteenth century – generated ‘darkness and loss’, an attractive setting for Gothic novelists such as Wilkie Collins and Bram Stoker in the nineteenth century and Daphne Du Maurier in the twentieth.

The Cornish Gothic is illustrated via three chapters. The first focuses on Du Maurier and in particular her novel My Cousin Rachel to identify ways in which Cornwall is represented in fiction as a Gothic territory – its landscape remote, hidden, possessive, mysterious, odd, strange, animated, ungraspable, other (p.23). Both the strangeness and the doubling are then traced in other fiction, including the film Bait (2019), where a pervasive sense of tension and unease becomes Gothic ‘strange fiction’.

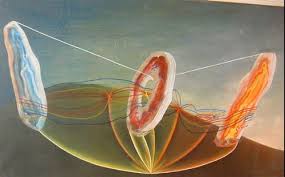

The second chapter takes as its central subject the less well-known psychomorphological work of painter, poet, writer and occultist Ithell Colquhoun. Colquhoun’s ‘strange’ art is understood here as Gothic and used as a springboard to spiral off into a discussion of magic, earth mysteries, paganism and eco-feminism. This collection of new age ephemera cohered around Cornwall in general and West Penwith in particular at the close of the last century and is seen here as a quintessential part of the Cornish Gothic.

The final section of the book discusses the debt owed by the Gothic to folk horror and the central role of Cornwall in this, playing to fears of otherness, paganism and sacrifice, both animal and human. David Pinner’s Ritual (1967) is the central text here. Although the book was set in Cornwall the film based on it – The Wicker Man – was moved to another periphery in Scotland. Folk tale collectors such as Bottrell and Hunt may be bemused to discover that they played a central role in the development of a ‘generic folk horror grammar’. This is one where Cornwall, its supposed ‘old ways’ never entirely erased, had a central place. In these ‘old ways’ of rituals and witchcraft, the sea has a special, indeed central, place in the Cornish Gothic, an ‘othered realm hostile yet providing’ (p.68).

While Tanya Krzywinska and Ruth Heholt succeed in evoking the ‘special and strange’ imagery of Cornwall constructed by the Gothic gaze and do an excellent job in restoring the Cornish Gothic to its proper place within Gothic Studies, there remain some problems with the concept of the Cornish Gothic. In Gothic Studies more generally at times there is potential for considerable conceptual confusion. For example, there is surely a potential issue of slippage – from signifier to referent, from the imagination of Cornwall to the material reality of Cornwall. This slippage from the imagined to the real may not be significant from the point of view of the Cornish Gothic critic. The distinction is inevitably blurred as part of its approach and that might just be the point. Yet, it remains at times confusing for the realist reader and has consequences for the credibility of the Cornish Gothic approach.

For instance, Krzywinska and Heholt assert that ‘access from England proves difficult’ and a ‘sense of isolation persists’, while Cornwall’s ‘wild beauty’ has attracted a host of dreamers – artists, writers, photographers and film makers (p.4). Is this part of the Gothic imagination of Cornwall or do they really believe Cornwall is ‘isolated’ and ‘wild’? It’s not clear. ‘Isolation’ and ‘wild beauty’ seem to be a little at odds with the growing issue of traffic congestion and pollution, ‘overtourism’ and the highest housebuilding rate in the UK, together with a persistent, unsustainably high population growth rate experienced since the early 1960s.

On this account, the Gothic might appear to be just another form of the Romantic. Krzywinska and Heholt admit that the two genres – the Romantic and Gothic – found creative expression in the same period in the nineteenth century and the two were ‘never far apart’ (p.14), as in the writings of Du Maurier. Yet the Romantic has also been associated with a ‘sense of control and superiority’ (p.15). This is the ’prospect’ view of the margins. Krzywinska and Heholt cite Hughes’ words – the provincial becomes ‘that which is gazed upon by one who has the right to comment on it, rationalise it, render it familiar’ (2018, cited p.17). It’s the power of the centre to comprehend and contain the other. Is the Gothic critique any different, other than making the provincial irrational and rendering it unfamiliar? Furthermore, in the Romantic gaze the voice of those gazed upon is rarely heard. Does the Gothic scholar, any more than the Romantic novelist, provide any space for the voice of the subject of their gaze? Or are the latter merely the other, playing bit parts in mysterious rituals, anonymously propping up the bar in threatening taverns tense with potential violence, or grumbling incoherently at the tourist?

Finally, Krzywinska and Heholt cannot be faulted for their disarming honesty and self-reflexivity. They admit the role of incomers in the creation of a Gothic Cornwall, admitting that they too are ‘both incomers from the urban sprawl’ and acknowledging ‘we are instrumental in perpetuating its myth as a place of deep and subtle margins’ (p.73). Such honesty is refreshing but also raises the unresolved question of the impact of these myths on the insider, on the Cornish themselves. How far are we also complicit in the construction of such imaginations or myths? Or from another viewpoint complicit in our own colonisation? We await research on the extent to which we are actually touched by the Gothic. Or do we just regard the whole Gothic project as just, well … a bit ‘silly’.1

- cf. Tim Hannnigan, The Granite Kingdom: A Cornish Journey, 2023, p. 86. ↩︎

Shouldn’t that be ‘Gothick’?

LikeLike

Gothic music was certainly popular when I were a boy in Redruth. We were “othered” by the tourists, so we embraced it. Donning costumes and performing the other. The weird. The Montol. Like the Munsters, we identified as “not like you”. Cornish Gothic does reflect the jarring difference we feel to the wealthy incomers and tourists with their yachts and impeccable clothes; we have tatters and masks as we dance around the fire while they look at us all agog.

LikeLike